When Belbo disappears and then calls Casaubon for help, the latter realizes the Diabolicals believed in the Plan and kidnapped his friend to find the map. As he searches for his friend, he learns about Belbo was obsessed with a magical moment during his childhood and wanted to relive it helping to create the Plan.

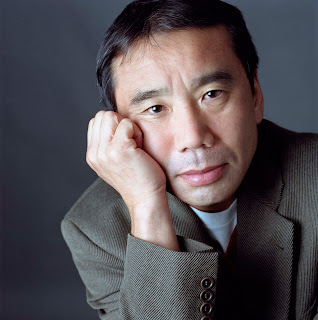

Foucault's Pendulum in Paris

In Foucault’s Pendulum, “the thinking man’s DaVinci Code,” the three friends remake history by manipulating texts and Eco satirizes the search for knowledge through historical documents. In his manipulating and interpreting historical texts, we can see Jorge Luis Borges’s influence, particularly his short story "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius." In this novel, Eco sows the seeds for his later novel The Prague Cemetery, where Simonini forges “historical documents,” particularly the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. To read Foucault’s Pendulum is to journey into the occultist society and to understand the how unreliable historical texts may be.

Foucault’s Pendulum is an Indiana Jones adventure without the snake pits, rolling stones, or Nazi treasure hunters, but with plenty of secret societies and conspiracies. I recommend this novel for the intellectual thrill and for the reflection on how we understand the past through historical documents.